The following article, published in the September-October 2015 NewsNotes, was written by John Martinez, a graduate student at George Mason University and intern with the MOGC’s Faith-Economy-Ecology project.

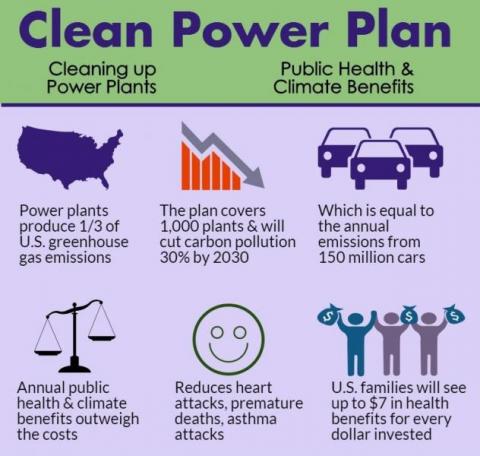

On August 4, President Obama unveiled the final version of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan (CPP), a set of national standards to reduce carbon emissions from U.S. power plants by 32 percent from 2005 levels by the year 2030. The White House touts the plan as a “strong and flexible framework” that will provide public health benefits such as preventing premature deaths from power plant emissions; will create tens of thousands of jobs by updating energy grids and switching to cleaner energy production; will drive investment in green energy resulting in 30 percent more renewable energy generation by 2030; and will lower the cost of energy enough to save U.S. residents $155 billion between 2020 and 2030.

An affirmed Clean Power Plan certainly will help the U.S. delegation at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) meeting to be held in Paris in December; it would show that the U.S. is serious and committed to fighting climate change, and would allow the U.S. to play a true leadership role in the talks. (See related article here.)

The White House claims that the Clean Power Plan keeps the nation on track to reduce emissions consistent with its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), the U.S. commitment to emissions reduction made as part of the UNFCCC process. Each country must pledge an INDC that is fair, equitable, and ambitious with an overall goal of keeping Earth’s temperature below 2 degrees Celsius as established at the UNFCCC meeting in Lima in December 2014.

However, the projected effects of the Clean Power Plan alone will fall short of meeting the U.S. INDC commitment of 28 percent emissions reduction by 2025. The New Climate Institute notes that the revised CPP still leaves a gap of about one billion tons of emissions between the CPP reduction goals and the U.S. INDC. In order to meet the INDC goal, President Obama and the subsequent administration will have to find other ways to reduce emissions, or hope that emission reduction as part of the CPP will drop faster than planned.

The plan proposes to achieve these emissions reductions by allowing the states to develop their own plans based on three “building blocks.” The first building block is to increase the efficiency of coal fired power plants, the second is to reduce emissions from coal plants by increasingly switching to gas fired plants, and the third is to increase the amount of energy generated by renewable sources.

The Clean Power Plan gives states significant flexibility in implementing emissions reduction, allowing them to either set their own emissions performance standards to meet their goals or to create state or regional emissions plans that could include mechanisms such as emissions trading, carbon taxes, renewable energy, nuclear energy, and improving energy efficiency. State compliance plans are due September 2016 with the option of an extension to 2018. The new standards are due to kick-in by 2022.

The response to the finalized plan has been mixed and has fallen along partisan lines. Coal companies and states that rely upon coal extraction oppose the plan, arguing that the regulations will result in increased energy costs for consumers as well as job reductions. The extent to which these claims may be true is debatable. An Analysis Group review of the Clean Power Plan proposal predicts that the impacts on electricity rates will be modest in the near-term and result in lower electricity bills in the long-term. Even the energy industry-funded Center for Climate and Energy Solutions predict in their analysis that consumer costs will be minimal. In terms of jobs, the green energy sector has grown to such an extent that, according to Politifact, today there are more U.S. citizens working in green energy than in the petroleum industry, and even more employed in the solar industry specifically than there are in the coal industry.

The response from many environmental organizations has been positive. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) hails the Clean Power Plan as a “game changer,” and credits the plan’s flexible implementation framework that allows states the freedom to make their own choices. The NRDC echoes other organizations in the belief that the key to implementing a plan that works is to give the states as many tools as possible with which to meet their goals.

Other environmental organizations, however, have a more grim reaction to the plan. Greenpeace recognizes that the Clean Power Plan is an important step forward, but describes it as “depressingly insufficient and unambitious.” Greenpeace notes the degree to which coal, oil, and gas development has expanded under the Obama administration, and concludes that the administration has been “playing with numbers” in order to make the plan appear more ambitious than it actually is. They note that the choice of the year 2005 as the benchmark from which emission reductions will be measured is convenient, as 2005 marked the absolute peak of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. As of 2015, emissions have already fallen 15.4 percent compared to 2005 levels, which means that under the CPP the rate of national emissions reduction will actually slow down in the coming 15 years compared to the previous 10.

Even if the Clean Power Plan contains a degree of number massaging and hype, it is still considered unacceptable to congressional Republicans. The implementation of the plan has been fought in Congress and in the courts, and will continue to be fought for years to come. For example, Republican Senator Shelly Moore Capito from West Virginia, a state heavily influenced by the coal industry, responded to the announcement of the final CPP by submitting a bill to allow states to opt-out if it is found to impact such broadly defined areas such as economic growth and electricity rates.

Legal and political hurdles such as these will have to be addressed and overcome if the U.S. wants to make a good-faith argument to the world that it is serious and committed to fighting climate change.