The following reflection was written by Merwyn de Mello, returned Maryknoll Lay Missioner, for the Nonviolence and Just Peace conference held in Rome, April 11-13, and published in the July-Agusut 2016 issue of NewsNotes.

From 1994–2013 I served as a Maryknoll Lay Missioner in Japan, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and the United States. Since 2014, as a Mennonite Central Committee international service worker based in Kabul, Afghanistan, I am an advisor to the peacebuilding project of International Assistance Mission (IAM), a Christian NGO, with a 50-year presence in country.

My journey in faith brought me to Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is a country plagued by war over the last four decades. Shows of strength and power exacerbate and protract the cycles of violence that have direct, structural and cultural manifestations.

Direct violence is most visible in the active fighting between government forces and/or local security forces and armed opposition groups in many of Afghanistan’s provinces. Structural violence can be seen in the judicial system when rulings are overturned without due process and in governmental institutions where power and wealth are consolidated into the hands of a few who determine how the needs of those with less power are met.

Cultural violence can be seen in the attitudes and beliefs that legitimize direct and structural violence. In Afghanistan, because of four decades of intense violence, people under 40 years of age have not known peace. Violent solutions to conflict are witnessed daily. For example, a study by the United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) showed that 92 percent of Afghan women believe that husbands have the right to beat their wives.

The perpetration of violence does not happen in isolation.

Each act of violence is often linked directly to a previous experience of violence. Individuals, communities, and whole societies can be caught up in cycles of violence, unless deliberate steps are taken to break out of the cycle.

The culture and philosophy of active nonviolence shapes our Peacebuilding Project activities dedicated to the goal of greater peace and stability in Afghan homes, communities and organizations. We look for pathways for peace in Afghan culture, traditions and faiths.

Participants tell us they not only value diversity in their communities, but also accept, appreciate and celebrate it. Afghan society is characterized by diversity. There are seven major ethnic groups and two main languages, and numerous minority ethnic groups and languages.

Islam is the national religion, but Sikhism, Hinduism, Judaism and Sufism are also present. Among Muslims, the majority are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school, a smaller number of Shi’a, and few Twelver (Imamis) and Ismaili Muslims. Afghanistan has been able to hold its ethnic diversity in balance for centuries, possibly through oppressive means, but also through networks of relationships that emerge when people live in close proximity. Throughout our work, we are sensitive to the need for building a language and a culture of diversity in Afghanistan.

Our work integrates concepts of trauma healing and cycles of violence into our peacebuilding curriculum. Trauma for Afghans often involves lack of food and water, lack of shelter, imprisonment, serious injury, sudden fleeing, forced separation from family, murder of family members, and rape. We partner with organizations that have community mental health programming to connect individual trauma healing and collective healing from historical trauma.

Participants use conflict resolution skills in their day-to-day lives, especially to address tensions between traditional and modern cultural norms. We promote indigenous methods and tools that are culturally and religiously appropriate. We incorporate Islamic principles of nonviolence into our peacebuilding work. We promote incorporating peacebuilding processes into Shuras and Jurgas, community-based institutions that are intertwined with the lives of people in Afghanistan.

To promote the teaching and practice of nonviolence in the Catholic Church, we need to:

- Examine our structures and social hierarchy to find areas that need to be turned upsidedown for the practice of nonviolence to take root;

- Work in partnership with faith traditions that practice nonviolence in order to institutionalize the principles and practice of nonviolence in Catholic institutions;

- Connect people practicing nonviolence at all levels of society in order to promote a web of change agents that fosters a culture of nonviolence;

- Invest in building a ‘stock exchange’ of people and resources to be freely accessed as needed, particularly in conflict areas.

Fath in action:

- Sign the appeal to the Catholic Church to re-commit to the centrality of Gospel nonviolence, the final statement of the landmark Nonviolence and Just Peace Conference held in Rome in April 2016;

- Follow the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, of which the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns is a part, to support more nonviolence teaching and actions in the Catholic Church.

- Sign up to receive action alerts and newsletters about issues of peace and justice from the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns.

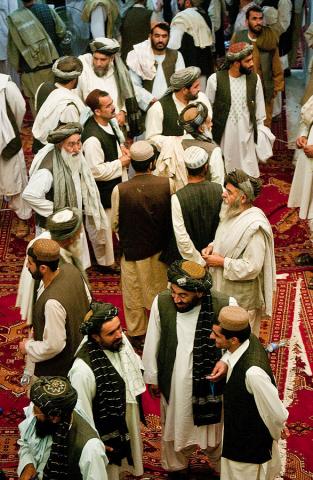

Photo: Men wearing traditional Afghan dress in the southern city of Kandahar, Afghanistan. Photo in the public domain and available via wikimedia commons.