The following is an update on the article Bolivia: Highway plan stokes conflict, published in the November-December 2011 issue of NewsNotes.

Ceding to demands from indigenous communities in October 2011, the government of President Evo Morales stopped the construction of a highway through the Isiboro-Secure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS in its Spanish acronym) and declared it an "untouchable" ecological reserve. The controversy is not over, however; the government, which hopes to re-start the highway's construction, has proposed an official consultation of affected indigenous communities as required by Bolivia's new constitution and international agreements.

The consultation will be limited to the Mojeño Trinitario, Chimán and Yuracaré peoples who live in 63 communities on the TIPNIS reserve. The votes will not be individually taken, but made collectively by each community according to their traditions. More recently arrived indigenous groups, mostly from the highlands, who have settled into a nearby area called Polygon 7 and are more supportive of the highway, will not be consulted.

As Emily Achtenberg of the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) writes, the consultation has sparked more controversy and confusion for a variety of reasons. "First, the TIPNIS consultation process will be anything but 'prior,' since the construction contract and funding agreement for the road [with Brazil's National Bank] have long been executed." It is also not clear how binding the result will be. Some legislators from Morales' own MAS party have implied that a result against the highway will not be binding and the government still retains the right to choose its course of action. "Finally, many say that the TIPNIS consultation process can't be carried out in 'good faith,' since the government responsible for implementing it is an interested party, strongly advocating for the road."

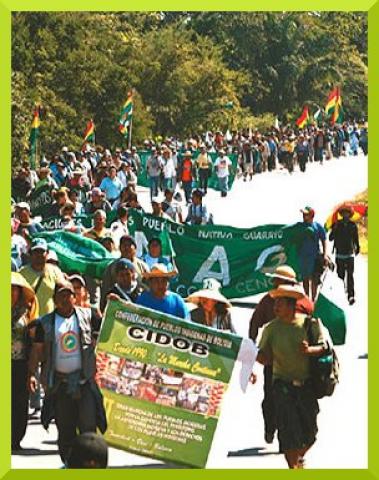

An unofficial "pre-consulta" of 35 of the communities shows that 32 will vote against the road. Despite the clear indication of victory, CIDOB, the lowlands indigenous federation that represents many of the groups against the road, has called for another march to the capital that will likely be at the time of the vote, which must be held by early June (within 120 days of the promulgation of the law calling for the consultation.) They want the TIPNIS to remain untouchable and worry that the consultation is being used to undermine that law.

The sensible compromise promoted by Pablo Solon, Bolivia's former ambasssador to the United Nations, is being overlooked by the government: Solon has called for a commission composed of representatives from indigenous communities, the governors of Beni and Cochabamba, and the national government, together with engineers and environmentalists, to study alternative routes for the highway, considering the potential economic, environmental and social impacts.

"Only on the basis of all these alternatives is it possible to then carry out a serious and responsible consultation," said Solon. Unfortunately, with the 120 day timeline, it is unlikely the studies will be carried out, and the situation will remain unresolved, with a possible solution pushed further into the future.