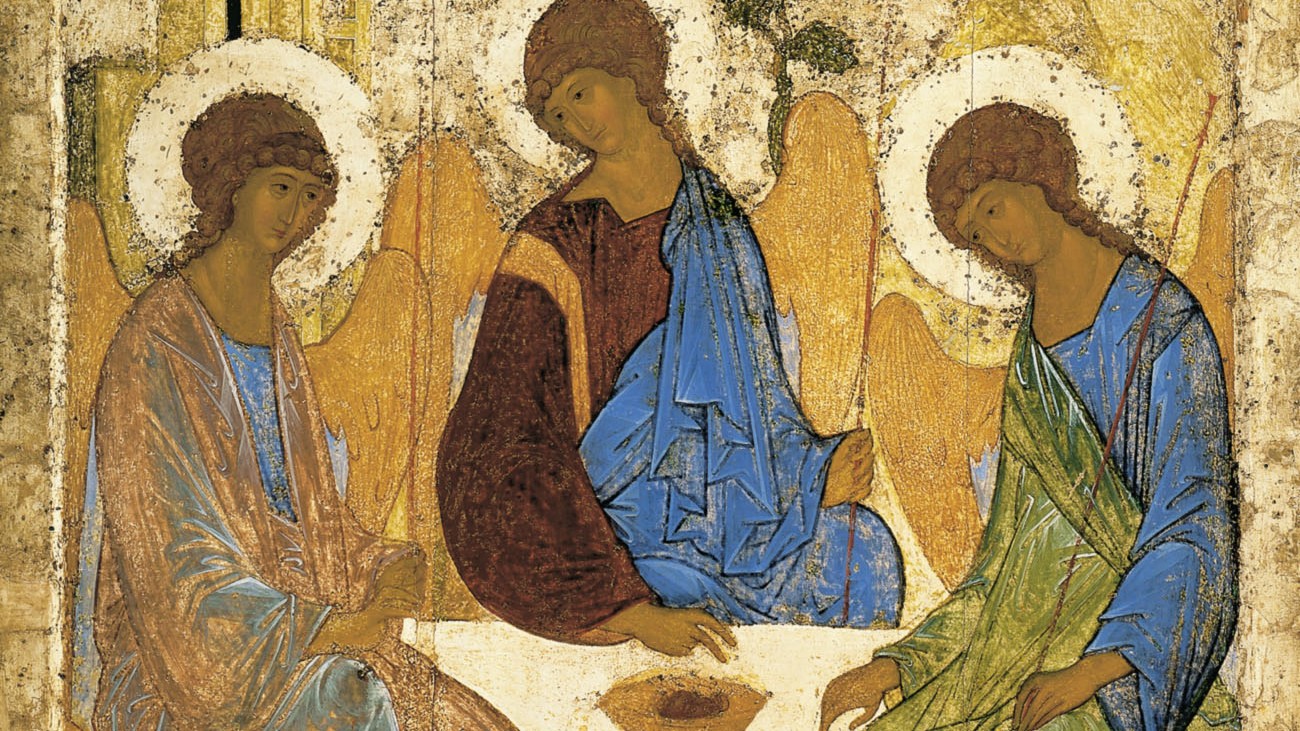

Painting “Trinity” by Andrei Rublev via WikiMedia Commons.

Fourteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time

Fr. John Keegan, M.M.

July 6, 2025

Is 66:10-14c | Gal 6:14-18 | Lk 10:1-12, 17-20

“The Lord appointed a further seventy-two and sent them in pairs before him…. Say to them, ‘The reign of God is at hand.’”

The seventy-two, sent in pairs by Jesus, are to say: “The reign of God is at hand.” What can that phrase, “the reign of God,” possibly mean? Perhaps, it is a way of calling attention to God’s transforming presence when it is breaking into human life in this universe. In any case, there are some curiosities to be noticed in how that presence makes itself visible.

First, the “reign of God” happens within a context. It breaks in when persons move to and travel toward other persons. It becomes present when those who are sent are welcomed and find hospitality. Secondly, the “reign of God” is not located in the interior of an individual life, or in some privacy of relation with God. It has a social shape. Those who are sent come two by two to people in the plural. The “reign of God” longs to become visible as a “church,” people gathered together in hospitality “giving thanks to the God they now dare to call ‘Father.’” Finally, although the ones who are sent may have been sent “as lambs in the midst of wolves,” God’s transforming presence will not reveal itself where it is not welcomed. Strangers received in peace, foreigners shown hospitality; these are the prerequisites that ultimately lead to table fellowship with God – the great banquet to which all are called, and to which the Eucharist points when hospitality allows it to be celebrated.

Maryknoll missioners certainly know this. They arrive in so many different places as foreigners and strangers. But, when they are welcomed, God’s transforming presence breaks in, gathering them and their hosts together into “church.” Welcoming strangers is the surest way of opening a way for God’s transforming presence to move within human life in this universe. In God’s reign there “are no longer strangers and sojourners, but… fellow citizens with the holy ones and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the capstone.” (Eph. 2, 19-20)

Even more! Christian tradition has woven into it this theme: when we welcome strangers, we allow the presence of God to become visible. The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews counsels us, “Do not neglect hospitality, for through it some have unknowingly entertained angels,” those forerunners of God’s presence. Later, around 1410 A.D., the eastern artist, Andrei Rublev would create one of the great icons of Christian art. It would depict the three strangers Abraham welcomed to his tent by the terebinth of Mamre. (Gen. 18, 1) But Rublev removed the figures of Abraham and Sarah from the scene, and through a subtle use of composition and symbolism caused us to focus on the three strangers as a way of imagining the mystery of the Trinity.

Why is this reminder of Christian tradition important? Perhaps a sentence from John Berger’s, In Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos will explain. He writes, “This century, for all its wealth and with all its communication systems, is the century of banishment.” Is he not pointing to something negating the “reign of God?” Is he not making us aware of the prevalence in our midst of a hostility to strangers insinuating itself into our lives? Witness the recent laws and political rhetoric in our own country whose aim is to penalize immigrants. We refuse to recognize people looking for asylum and call them “illegals”, or “undocumented.”

Every celebration of the Eucharist is a good time to remember something central to our Christianity, especially to its catholicity. We are the people who welcome “open borders” between people. Our religious tradition has a long memory. It remembers a time before passports and visas were ever needed if one wanted to travel. It remembers that the nation-state, with its closed defensible boundaries, is simply an invention of the European Peace of Westphalia in 1648. It remembers a time when human beings were not denied “freedom of movement.” and it imagines a time in the future when it will be true again.

We occasionally forget how important “freedom of movement” is to human rights. There are, no doubt, numerous human rights, but, ultimately, they all have their foundation in a basic core. Every human being has the right to subsistence and the right to be secure, free from terror. Only an unjust nation-state would violate subsistence and security rights. But, “freedom of movement” is the right fundamental to their well-being. It is “freedom of movement” that makes subsistence and security important rights to be enjoyed precisely as rights. Without it, they may be had, but they can not be enjoyed as rights. They may be had as privileges, discretions or indulgences from a governing state, but not as rights. Without “freedom of movement” they do not belong to a human being because of his or her dignity and value as a human in the family of humankind.

Every Eucharist is a gathering together of people to give thanks at the table of the Lord. That gathering together is built on hospitality, on welcoming strangers. There, together with Paul, we do not “boast of anything but the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.” May our gatherings be a sure antidote to “the century of banishment.” May all feel welcome.