Encounters #6: Moving into the collaborative economy

June 2015

* Encounters has been edited to correct the references to Marco Fioretti.

The book of Acts is all about building community: working together to spread God’s love through acts such as getting rid of all unnecessary personal items, feeding those who are poor, and caring for the sick. Acts concludes with Pentecost when people speak in unison through a variety of languages. It is through building strong and resilient communities that we can truly experience God’s love.

In the context of our work to build a new creation, the “collaborative economy” is one vehicle to build community and allow the spirit to flourish. In the last Encounters, we explored the “sharing economy,” which is one aspect of the collaborative economy, a movement that is beginning to displace large corporations by using technology to democratize many aspects of business — industrial production, research and development, and a wide variety of amenities including financial services. In this issue, we explore these other aspects: distributed production, peer-to-peer financing, and open source knowledge.

Distributed production

Corporations usually consider their customers to be passive recipients of the expertise and resources of professional service providers. However, as many movements and organizations around the globe have shown for decades, the customers have much to offer. They have their own knowledge, experience and capacity to design and contribute to services that respond to their needs more effectively as well. Undoubtedly, a paradigm shift is on the horizon, and the implications for more democratic production are profound.

New technologies offer unprecedented means for small-scale, distributed production. Due to the growing accessibility of tools including 3D printers, laser cutters and open source designs and hardware, many people are enabled to create their own products. This “maker movement” is poised to transform our economy by empowering everyday people and small business owners to design and manufacture their own creations. In the words of Co-production Wales, a voluntary alliance of individuals and organizations whose vision is to put co-production at the heart of public services: “[T]his phenomena enables citizens and professionals to share power and work together in equal partnership, to create opportunities for people to access support when they need it and to contribute to social change.”

Despite its simplicity, this idea has revolutionary potential: instead of being concentrated in the hands of mammoth corporations, resources are distributed and redistributed via a system that is both efficient and equitable on a local, regional, national and global scale.

By lowering marginal costs, the distributive economy promotes a fair sharing of assets that benefits society as a whole. The entertainment industry is a good example: today, a growing number of people are producing and sharing videos and music on relatively cheap cellphones and computers at nearly zero marginal cost in a collaborative networked world. With the massive amounts of energy required to make computer chips, some question whether this trend, which is so technology-reliant and therefore dependent on cheap energy, is sustainable in the long run, especially if one takes into account the probability of surpassing peak energy production in coming years. But it is clear that an increasing portion of the economy is beginning to feel the impact of distributed production.

While stock exchanges originally provided a public service by allowing companies to raise money from a large number of investors by selling shares of ownership, today capital formation is a small part of what happens in stock markets. According to John Fullerton, former managing director at JP Morgan and founder of the Capital Institute, an organization dedicated to making capital markets more sustainable and socially beneficial, “Today’s stock markets are primarily about speculating on the future prices of stock certificates; they are largely disconnected from real investment or what goes on in the real economy of goods and services… recent history has shown that our world leading liquid markets are as well the source of extreme global instability with dire and ongoing consequences.”

Fullerton cites a variety of reasons why stock markets are no longer as beneficial to society as originally envisioned:

- The privatization of stock exchanges, destroying their public purpose mandate and instead making the growth of trading volume their single-minded goal and high-frequency traders (computers programed to trade) their preferred customers;

- The unrestrained technology arms race in computing power combined with the adoption of technology-driven information flow spurring the rapid acceleration of trading volume, which at critical times can be highly destabilizing;

- The misguided ascent of “shareholder wealth maximization” (at the expense of all other stakeholder interests) in our business schools, board rooms, and the corporate finance departments on Wall Street;

- The well-intended but equally misguided practice of using stock-based incentives, and stock options in particular, as the dominant form of senior management compensation, which incentivizes them to focus only on short-term results at the expense of the long-term health of the enterprise, people and planet;

- The misalignment of interests between short-term focused Wall Street intermediaries and real investors such as pension funds whose timeframe should be measured in decades;

- Regulators’ lack of courage and confidence to counter the trader-driven paradigm and institute substantive structural reform such as a Financial Transactions Tax and other reforms that would penalize excessive speculation while incentivizing long-term productive investment.

For many years, people of faith have tried to live out their faith values by channeling their savings into socially responsible investments (SRI) in which they avoid buying stocks in businesses that make weapons, alcohol, or extract fossil fuels, and instead invest in companies that are ecologically sensitive, treat their workers well, etc. depending on that investor’s values.

Some may be surprised to know that buying stock in a corporation brings few real benefits to that company. After the initial public offering (IPO) when a corporation first sells shares, subsequent buying and selling of shares don’t bring additional money to the firm other than through secondary offerings that are rarely used as they dilute the value of the stock. Minimally, investments contribute to a higher stock price, but the benefits to a corporation from this increased price are relatively small – mostly easier access to credit and protection from being “taken over.” As Fullerton points out, those most interested in high stock prices are CEOs and management who increasingly receive stock options as part of their salaries.

People who are looking for other opportunities to invest may consider new avenues that support the birthing of a new economy. The vision of this new economy is more democratic, equitable, and environmentally sustainable. With the advent of new technologies, a host of alternative forms of investment are now available that can provide financial returns while more directly benefitting society.

| Corporate accountability: One way faith communities have become more active in influencing corporations’ actions is through shareholder activism: Foundations, endowments as well as individuals, buy stock – often at the minimum number of shares — in a corporation not in order to profit from its dividends, but with the goal of influencing the corporation through shareholder resolutions or proposals. Many religious organizations, including the Maryknoll Fathers & Brothers and the Maryknoll Sisters, are members of the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility (ICCR), which offers shareholder proposals to compel management to take an action in a variety of areas from executive compensation to implementing greener processes or improving working conditions. At corporations’ annual meetings of shareholders, these proposals are considered and voted upon by all shareholders. |

Peer-to-peer lending

The proposal of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending is to democratize finance by using Internet platforms to directly match people in need of a loan with those with money to lend and looking for higher returns than other investments. By cutting out banks as intermediaries, the platforms are able to provide lower interest rates for borrowers and higher returns for lenders while disrupting the oligopoly of a shrinking number of financial institutions.

Yet, as we witness with the sharing economy, large financial institutions are coming to dominate peer-to-peer markets as well. According to The Economist, “[i]n America [sic], the two largest P2P lenders, Lending Club and Prosper, have 98 percent of the market” and an increasing amount of the money loaned on these platforms comes not from individual lenders but from hedge funds and large banks – “only a third of the money coming to Lending Club is now from retail investors.” In her aptly titled article, “Wall Street is hogging the peer-to-peer lending market,” financial reporter Shelly Banjo refers to a study by Orchard Platform showing that “all of the loans made by Lending Club and Prosper in 2008 were fractional, meaning individual lenders came together and each put in as little as $25 toward a loan. Now, only 35 percent of the loan dollars are coming from fractional loans. In 2014, the other 65 percent of the more than $3 billion loans on the two platforms came from investors snatching up whole loans, which are almost always made by institutional investors rather than individuals.” Photo from Lendingmemo.com.

Yet, as we witness with the sharing economy, large financial institutions are coming to dominate peer-to-peer markets as well. According to The Economist, “[i]n America [sic], the two largest P2P lenders, Lending Club and Prosper, have 98 percent of the market” and an increasing amount of the money loaned on these platforms comes not from individual lenders but from hedge funds and large banks – “only a third of the money coming to Lending Club is now from retail investors.” In her aptly titled article, “Wall Street is hogging the peer-to-peer lending market,” financial reporter Shelly Banjo refers to a study by Orchard Platform showing that “all of the loans made by Lending Club and Prosper in 2008 were fractional, meaning individual lenders came together and each put in as little as $25 toward a loan. Now, only 35 percent of the loan dollars are coming from fractional loans. In 2014, the other 65 percent of the more than $3 billion loans on the two platforms came from investors snatching up whole loans, which are almost always made by institutional investors rather than individuals.” Photo from Lendingmemo.com.

Some market analysts say that large institutions are necessary in order to scale up to provide needed capital, but the reality today is that “investor demand is now outstripping the loan supply, spurring fierce competition among investors to snatch the best loans first,” according to Amy Cortese in the New York Times. Orchard Platform has shown that these investors are now snapping up nearly 50 percent of whole loans on Prosper in less than 10 seconds by using complicated computer algorithms similar to those used by high-speed traders in other capital markets. These algorithm-armed investors end up scooping up all of the highest quality loans (the ones most likely to be paid back) leaving the poorest quality loans for everyday investors whom P2P lending is supposed to benefit.

While the larger P2P lending platforms have been bought out by the same banks and hedge funds that peer lending was supposed to replace, at least one large-scale platform has maintained fidelity to the idea of individuals helping other individuals: Zopa, the world’s first peer-to-peer lending platform and currently the United Kingdom’s largest. Since its inception in February 2005, Zopa has facilitated more than $1 billion in loans, all between individuals, showing that institutional money is not necessary to scale up a P2P lending platform. While few of the larger P2P platforms remain purely peer-to-peer and have essentially been taken over by the same financial system they were designed to replace, there are a number of other ways to invest savings without becoming participating in the overgrown financial system.

Direct public offerings

Many small and medium-sized businesses have a difficult time raising money, as they are too small to attract large investors, yet also too big for other sources such as family and friends. The Small Business Administration (SBA) estimates that the aggregate amount needed by businesses seeking between $250,000 and $5 million to be $60 billion. The problem is so common that the SBA created a term, “capital chasm” to describe it. Increasingly, these businesses are using the Internet to sell shares of ownership directly to investors without the aid of an investment bank or broker that charge massive fees and are rarely interested in financing smaller enterprises.

For investors, a direct public offering means that more of their investment goes directly to the business instead of being siphoned off by an investment bank and as they are buying public shares, they can pull out of the investment at any time by selling their shares. Cutting Edge Capital lists a number of entities that facilitate direct public offerings.

Evergreen Direct Investment Method

Capital Institute founder John Fullerton, the former JP Morgan executive, notes that conscientious investors in the responsible investing movement “seeking to embed environmental, social and governance values (ESG) into their investment decision-making are hamstrung by the investment method chosen. Specifically, trying to apply ESG to what is inherently a speculative stock valuations game often feels like pushing on a string. Without conscious awareness, we have confused speculation for investment.”

The Capital Institute proposes the Evergreen Direct Investment Method in which institutional investors like foundations and pension funds can build long-term relationships with enterprises that express their values and “can achieve attractive and resilient long-term financial returns that match their liabilities, while directly embedding ESG values into negotiated investment partnerships.” The method envisions, “stewardship-minded investors negotiating direct relationships with corporate management with an explicit requirement to build long-term environmental, social and governance values and parameters into the enterprise capital investment process, even if it entailed some short-term negative consequences.” The advantage is that investors can have a real say in the actions of a company while providing “stable cash flows of mature, slow- or no-growth business enterprises that the valuations-game-driven speculators leave on the trash heap.”

Slow Money

Slow Money is a movement that aims to “bring money back down to earth” by helping investors to “invest as if food, farms and fertility mattered.” They do this by connecting investors to small food enterprises throughout the U.S. From farm cooperatives to urban agriculture enterprises to manure farms and more, Slow Money has helped funnel over $40 million into more than 400 small farm efforts around the country.

Community and faith-based development investing

Another alternative to placing valued savings into the financial markets is to invest in community and faith-based development organizations that support local efforts to provide affordable housing, jobs and economic development, especially in low-income communities. These forms of investments provide an alternative rooted in the social justice values promoted by faith traditions.

The Mennonite Church USA established a stewardship agency called Everence that provides financial products and services that are aligned with their founding values. They have developed two programs for community investing: mPower, which provides funding for international microfinance organizations; and nSpire, which supports faith-based community development projects throughout the United States. The World Council of Churches established Oikocredit in 1968 to provide an ethical investment channel for churches and related organizations to provide credit to enterprises that support the disadvantaged. The Slow Money movement kindly provides a list of other community investment opportunities as an alternative to large financial institutions.

Church P2P lending

Some churches are helping their members dig themselves out of debt through low-interest loans. The United Methodist Church created the Jubilee Assistance Fund especially to help people unable to pay the exorbitant interest rates of payday lenders and others who take advantage of people with low incomes. By providing much lower interest loans, churches help their members avoid evictions, bankruptcies and other financial woes. This fund is grounded in the scriptural text that the fiftieth year should be a jubilee year when all debts are forgiven.

Catholic social teaching and the open source & knowledge movements

The free transfer and use of knowledge and technology is becoming increasingly important for human development. As Marco Fioretti writes in an interesting piece titled, Catholic Social Doctrine and the Openness Revolution: Natural Travel Companions? “Software is not a stand-alone industry or set of tools. It is something that makes every other physical or immaterial economic activity work, from agriculture to space travel and to every service from mere bureaucracy to healthcare, education, tourism, and lotteries.”

He goes on to show that though Catholic social doctrine has not referred to intellectual property specifically until very recently, it has favored the ideals behind open source technology. In “Rerum Novarum,” written in 1891, Pope Leo XIII (left) writes that private ownership, while necessary, brings to an owner the duty to be a “steward of God’s providence, for the benefit of others,” that must make property fruitful and communicate its benefits to others. [EDITED TO CORRECT REFERENCE TO MARCO FIORETTI.]

He goes on to show that though Catholic social doctrine has not referred to intellectual property specifically until very recently, it has favored the ideals behind open source technology. In “Rerum Novarum,” written in 1891, Pope Leo XIII (left) writes that private ownership, while necessary, brings to an owner the duty to be a “steward of God’s providence, for the benefit of others,” that must make property fruitful and communicate its benefits to others. [EDITED TO CORRECT REFERENCE TO MARCO FIORETTI.]

“In 1967, Pope Paul VI confirmed in ‘Populorum Progressio’ that all people are called to fulfillment and to a sharing in the good things of the Earth and all other considerations in economics must be subordinated to this principle.” Pope John Paul II wrote more specifically about the transfer of knowledge in 1987 with “Sollicitudo Rei Socialis”: “Forms of technology and their transfer constitute today one of the major problems of international exchange and of the grave damage deriving therefrom. There are quite frequent cases of developing countries being denied needed forms of technology or sent useless ones.”

Finally in 2009, Pope Benedict XVI was the first to refer to human problems because by the lack of freely accessible intellectual property in “Caritas in Veritate”: “On the part of rich countries there is excessive zeal for protecting knowledge through an unduly rigid assertion of the right to intellectual property, especially in the field of health care.” He stressed the importance of free gift for a healthy society: “The human being is made for gift … social and political development, if it is to be authentically human, needs to make room for the principle of gratuitousness as an expression of fraternity.”

We have addressed the importance of open source knowledge and the important advances made in this realm by the Free/Libre Open Knowledge movement in Ecuador, FLOK society, in a previous edition of Encounters. Current patent and copyright systems restrict innovation as much or more than they encourage it through creating unnecessary monopolies that create massive costs for society. The free transfer and use of knowledge is a crucial element of the Collaborative Economy that can help assure it remains accessible and democratic.

A public option

Economist Dean Baker, who has been critical of the Sharing Economy for its avoidance of important worker and public safety regulations, proposes a public option that could resolve many of these problems. “The idea is that governments can set up public sites that would provide the same services as the sharing economy companies. The difference would be that the public sites would cut out the middleman [sic]. They would be set up to benefit customers and service providers with the government only charging the fees necessary to cover costs.” “A public service could directly apply standards to providers as a condition of participating. Cab drivers would have to meet licensing standards and their cars would have to pass inspection. And they would have to arrange insurance for both car and driver. A public version of Airbnb could require that potential renters had their rooms inspected for fire safety and also provide copies of leases or condo agreements to ensure that these were not being violated by renting out rooms or whole units.”

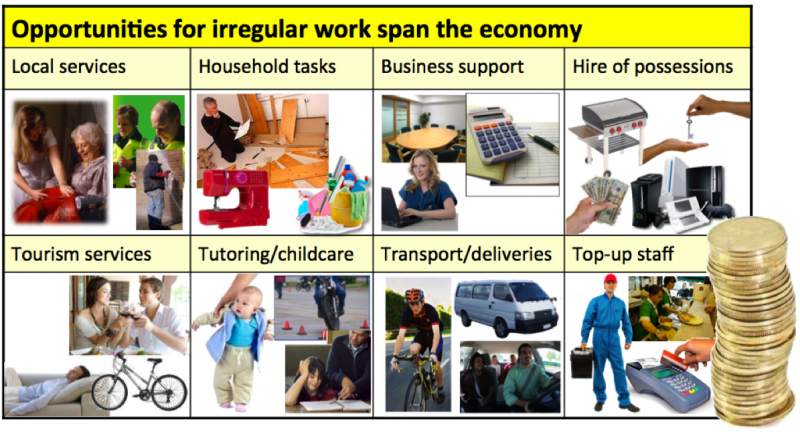

The British organization Beyond Jobs is doing exactly that by creating an open source program that helps link up workers who, for whatever reason, need work with irregular hours, with those wanting to hire qualified workers for temporary jobs. They are working with local and regional governments to implement the program.

The British organization Beyond Jobs is doing exactly that by creating an open source program that helps link up workers who, for whatever reason, need work with irregular hours, with those wanting to hire qualified workers for temporary jobs. They are working with local and regional governments to implement the program.

For distributed production, open access to projects that can be printed on 3D printers is fundamental. Numerous sites like Thingiverse catalog hundreds of thousands of free designs to be used by small producers anywhere in the world.

Conclusion

Michael Bauwens, founder of the FLOK society in Ecuador, explains, “Most economists argue that if everything were nearly free, there would be no incentive to innovate and bring new goods and services to the fore because inventors and entrepreneurs would have no way to recoup their up-front costs. Yet millions of prosumers are freely collaborating in social Commons, creating new IT and software, new forms of entertainment, new learning tools, new media outlets, new green energies, new 3D-printed manufactured products, new peer-to-peer health-research initiatives, and new nonprofit social entrepreneurial business ventures, using open-source legal agreements freed up from intellectual property restraints. The upshot is a surge in creativity that is at least equal to the great innovative thrusts experienced by the capitalist market economy in the twentieth century.”

The innovations being used to facilitate the exchange of goods and services directly between people without the intervention of large corporations have the potential to fundamentally shift the global economy toward a more democratic and horizontal model. As Bauwens puts it, “in a world in which more things are potentially nearly free and shareable, social capital is going to play a far more significant role than financial capital, and economic life is increasingly going to take place on a Collaborative Commons.”