The Great Green Wall of Africa

First proposed in 2007, the project to plant billions of trees along a 5,000 mile corridor in the Sahel of Africa is gaining momentum.

First proposed in 2007, the project to plant billions of trees along a 5,000 mile corridor in the Sahel of Africa is gaining momentum. This article was published in the March-April 2021 issue of NewsNotes.

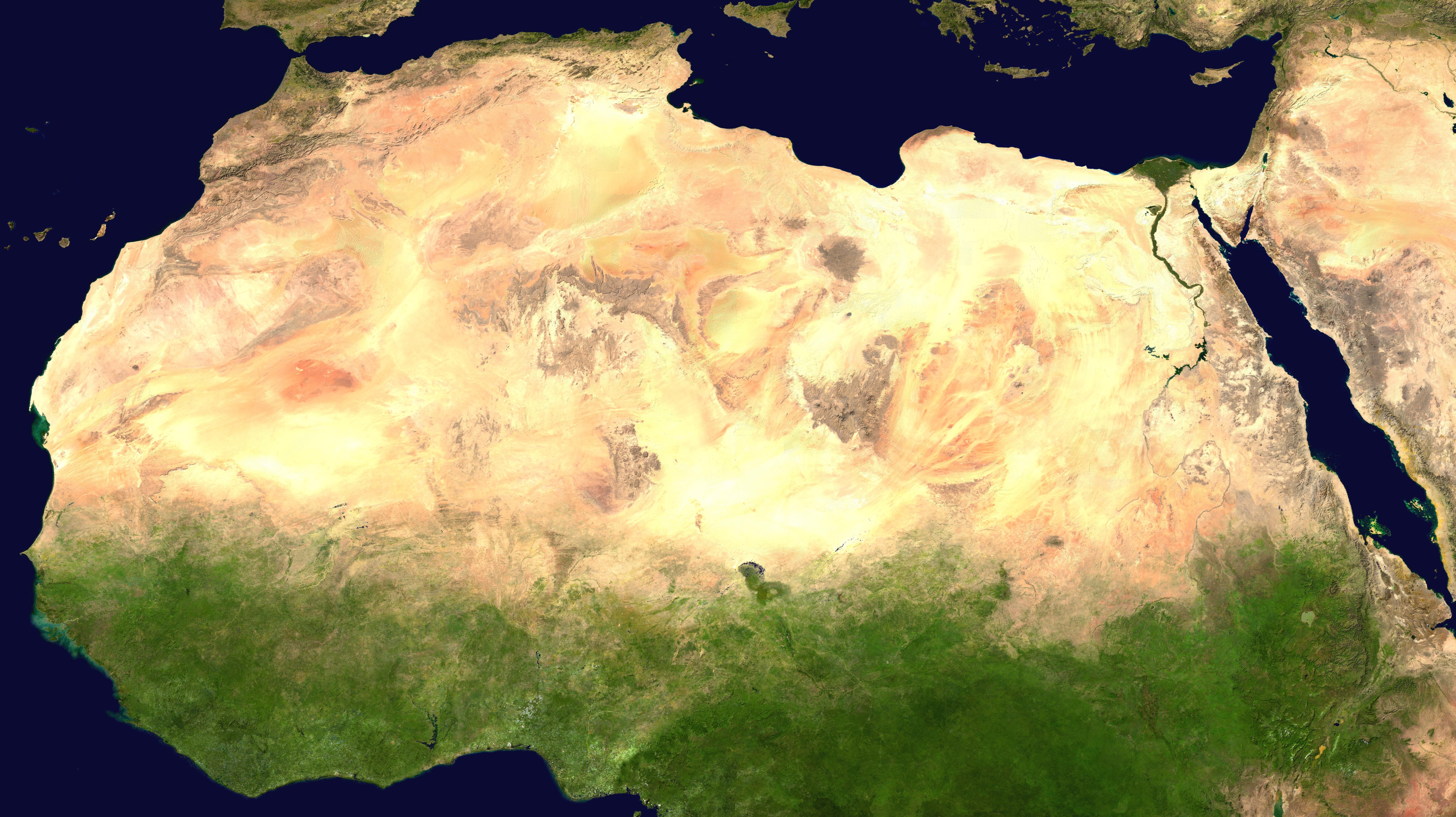

The Sahel is on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, stretching from the East coast of Africa to the West. One of the poorest places on Earth, and plagued with persistent drought, it is extremely vulnerable to climate change.

Begun in 2007, the Great Green Wall is an African-led project to plant billions of trees along the Sahel to robustly address three great challenges: to confront and prevent climate change; to halt land degradation and desertification in the Sahel; and to provide incomes for millions of people living in a dozen or so poverty-stricken countries in the region.

While proposals for a “green front” of trees in the Sahel are thought to date back to the 1950s, real planning for the project did not begin until the early 2000s. The project was approved in 2005 at a meeting of leaders of Sahelian States, and in 2007 the African Union (AU) officially launched it as the “Great Green Wall for the Sahara and Sahel Initiative.”

By 2030, the project aims to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land, sequester 250 million tons of carbon dioxide, and create 10 million green jobs. The AU means for the project to address the social, economic, and environmental consequences of land degradation and desertification in the Sahel.

Without urgent, concerted action, temperatures in the Sahel are projected to rise significantly faster than the world average, perhaps reaching four degrees centigrade (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than pre-industrial averages by 2030. Akinwumi Adesina, president of the African Development Bank and a leader of the project, stated the urgency of the project: “Without the Great Green Wall, the Sahel as we know it may disappear.”

The climatic stresses put on the Sahel have resulted in violent conflict, both between local farmers and pastoralists and in regional warfare between armed militias. Access to water resources is dwindling, the yields of subsistence farming are decreasing rapidly, and countless numbers of people continue to leave their homes to migrate into urban areas or embark on the risky trek to Europe. Restoring the Sahel as a place to live could prevent a huge wave of climate-induced migration in the coming decade.

In a National Geographic article, scientists involved in the project clarified that the project is not simply aimed at planting a wall of trees, but at carefully and naturally regenerating the landscape through various means. Tree-planting is one major strategy throughout the project, but each region within the Sahel will have its own specific plan for restoring the land and improving the livelihoods of residents.

Despite its lofty ambitions, as of 2020 less than one fifth of the designated land area has been restored or rehabilitated. The achievements so far mostly come from Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Senegal, which collectively have restored land or planted trees along 79 million acres of land – but even this is far from enough.

Cognizant of this stalling in the project, its leaders were able to accrue larger commitments of funding than originally anticipated at the One Planet Summit for Biodiversity held in Paris on January 11, with pledges totaling $14.32 billion over the next four years, of which the African Development Bank agreed to contribute $6.5 billion.

If successful, the project could have enormous impacts for people in the Sahel region, but it also could be a model for the global community of the power of natural and locally-driven solutions to climate change. “The Great Green Wall is a new world wonder in the making,” said Amina Mohammed, the UN deputy secretary general. “It shows that if we work with nature, rather than against it, we can build a more sustainable and equitable future.”

Photo: Satellite view of the Sahara, courtesy of NASA. Available via Wikipedia in the public domain.