G20 Summit in South Africa Holds the Line

Under threat of fracture, world leaders renewed their commitment to multilateralism while avoiding major decisions on debt relief for the Global South.

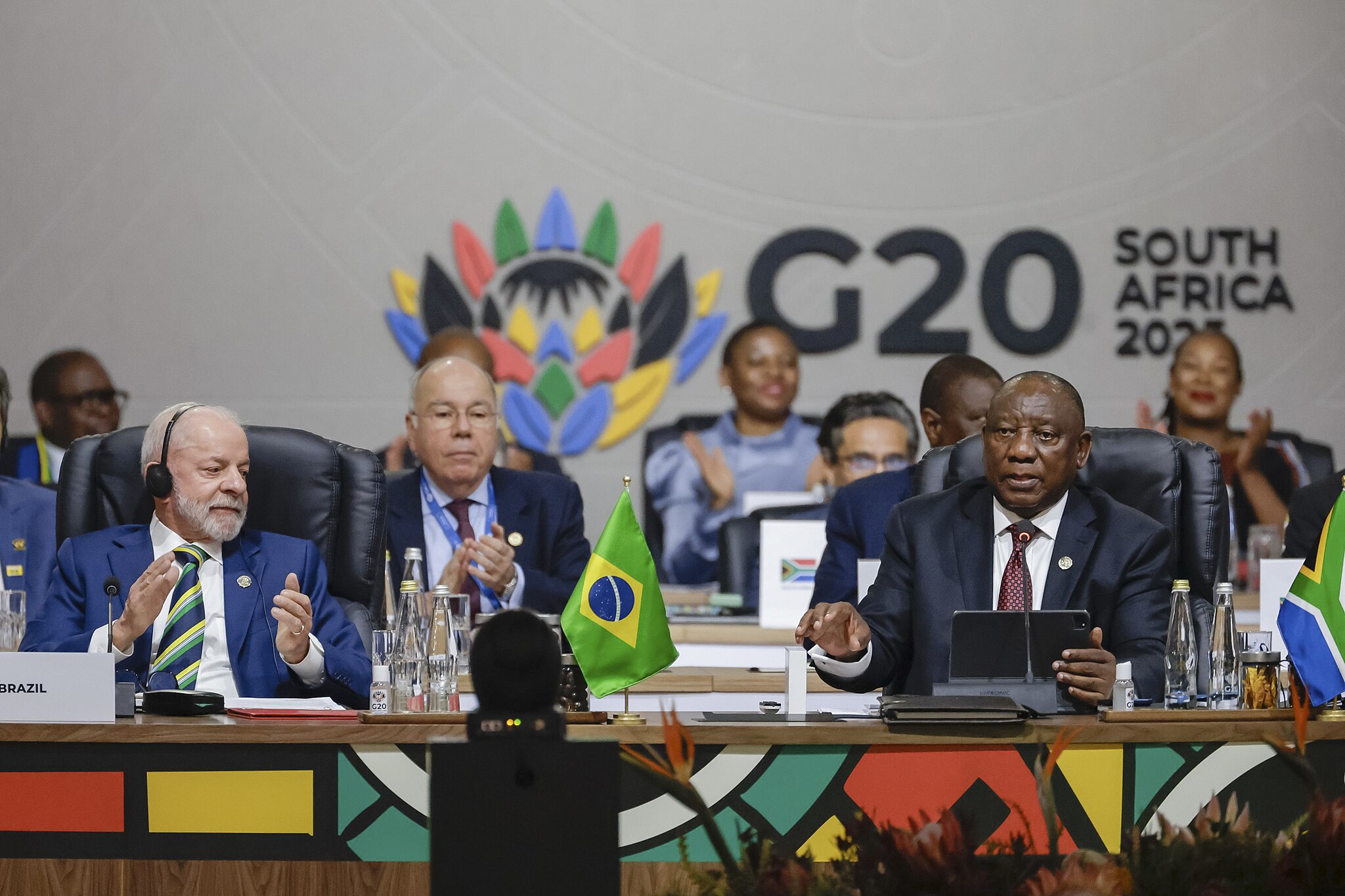

When leaders of the world’s major economies gathered in Johannesburg for the G20 summit in November—the first ever held on African soil—few expected consensus. Deep geopolitical rifts, mounting global inequality, worsening debt crises, and the unprecedented boycott by the United States all cast long shadows over South Africa’s presidency. Yet against the odds, the summit produced a leaders’ declaration supported by all G20 members present, marking a rare and fragile victory for multilateral cooperation in an era of fragmentation.

For many observers, the significance of the Johannesburg summit lies less in bold new commitments than in the fact that the G20 did not fracture. With the United States absent and openly warning other countries not to endorse the declaration, South Africa succeeded in rallying overwhelming support around shared language of debt, inequality, climate change, and development. As one analyst put it, in today’s geopolitical climate, “holding the line” may itself be an achievement.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa framed the summit as a moment to place the priorities of Africa and the Global South at the center of global economic governance. Those priorities are urgent. Across Africa, debt burdens have reached their highest levels in two decades, forcing governments to spend more on servicing loans than on health, education, or climate resilience. According to UN data, Africa’s public debt reached $1.8 trillion in 2022, while illicit financial flows and debt servicing together drain nearly $180 billion annually from the continent.

Against this backdrop, the G20 declaration’s recognition of debt distress matters. Leaders reiterated their commitment to improving the G20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments, calling for a process that is more “predictable, timely, orderly, and coordinated.” While modest, this language signals acknowledgment that the current system is failing. Since the framework was launched in 2020, only four countries—Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia— have completed debt restructurings, even as more than two dozen countries face debt crises.

Faith-based and civil society advocates have long argued that incremental reforms are not enough. Many debt justice advocates noted that the declaration stops short of proposing deeper, systemic solutions, such as a fair and transparent sovereign debt workout mechanism or stronger accountability for private creditors and credit rating agencies.

If the debt outcomes were limited, the summit broke new ground in elevating inequality. A G20-commissioned report described today’s situation as an “inequality emergency,” noting that since 2000, the richest 1% have captured over 40% of new global wealth, while the poorest half of humanity received just 1%. The report’s authors warned that extreme concentrations of wealth translate into extreme concentrations of power, undermining democracy and social cohesion.

One proposal to address this imbalance—a global inequality panel modeled on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—did not make it into the final declaration. Yet it quickly gained political momentum, with leaders from South Africa, Brazil, and Spain pledging to build a coalition to advance it. For advocates of economic justice, this represents a small but meaningful opening in a system that has long treated inequality as a secondary concern rather than a structural crisis.

Climate justice featured prominently in Johannesburg, particularly because the U.S. absence removed long-standing red lines. The declaration recognized climate change’s “urgency and seriousness”, reaffirmed the Paris Agreement, and emphasized the need for climate finance, disaster risk reduction, and adaptation support for vulnerable countries. U.S. absence and isolation may have made consensus easier in Johannesburg. Without the need to accommodate Washington’s objections, other leaders were able to move forward together, underscoring that multilateral cooperation is possible even when powerful actors step away.

At the same time, the future remains uncertain. With the United States assuming the G20 presidency, officials have signaled plans to narrow the group’s focus and sideline issues such as climate, health, and inequality. There is a real risk that the modest gains achieved in Johannesburg could stall or be reversed, particularly if key voices from the Global South are marginalized.

Still, the Johannesburg summit offers an important lesson. In a world marked by conflict, climate crisis, and widening inequality, spaces for dialogue and cooperation remain indispensable. The G20 is far from perfect, and it cannot substitute for more inclusive institutions like the United Nations. But when used strategically, it can amplify the voices of the Global South and keep justice-oriented issues on the global agenda.

Photo: 2025 G20 Summit, available in the public domain via Wiki Commons.