Catholic Church Responses to Authoritarianism in History

The Catholic Church and its members have served as crucial counterweights to oppressive governments throughout history, defending human rights under authoritarian rule.

The Catholic Church, with a moral mandate rooted in the inherent dignity of the human person, has historically played a vital and at times perilous role in the defense of human rights under authoritarian rule. While its institutional responses were not uniformly heroic—sometimes marked by quiet diplomacy or, in rare cases, unfortunate complicity—the consistent defense of fundamental liberties by the Vatican, bishops, religious orders, and lay organizations has provided a crucial bulwark against state terror.

This defense manifested in theological shifts, the creation of protected advocacy organizations, and the courageous personal witness of individual clergy and lay members.

Theological Shifts

Theological foundations for this activism were significantly strengthened by the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and its subsequent application through Liberation Theology, particularly in Latin America. Vatican II emphasized the Church’s engagement with the contemporary world and affirmed religious freedom as a cornerstone of human dignity. This was quickly adopted by Latin American bishops, who, at the 1968 Medellín conference, articulated a “preferential option for the poor.”

This theological shift positioned the Church not as an ally of the traditional elite, but as an advocate for the impoverished and marginalized, precisely the groups most often targeted by repressive “national security” regimes. This provided the moral and intellectual framework for actively challenging dictatorships in countries like Chile, Brazil, and El Salvador.

Protected Advocacy Organizations in Chile

Institutionally, the Church’s independent, global structure made it one of the few organizations capable of resisting state control and filling the void left by suppressed civil society. In Augusto Pinochet’s Chile, Cardinal Raúl Silva Henríquez demonstrated institutional cunning and courage. After the military regime forced the dissolution of the ecumenical Committee for Peace, Cardinal Henriquez immediately replaced it with the Vicariate of Solidarity in 1976.

Because the Vicariate was established as an internal department of the Archdiocese of Santiago, the dictatorship struggled to close it down without appearing to directly attack the entire Catholic Church, a move with significant diplomatic and international repercussions. The Vicariate operated as a legal and humanitarian shield, documenting human rights abuses, providing legal aid to the families of the disappeared and detained, and becoming a central repository of truth and resistance. Similar Church-backed organizations emerged across the continent, offering sanctuary and support where the law offered none.

Courageous Personal Witness in El Salvador

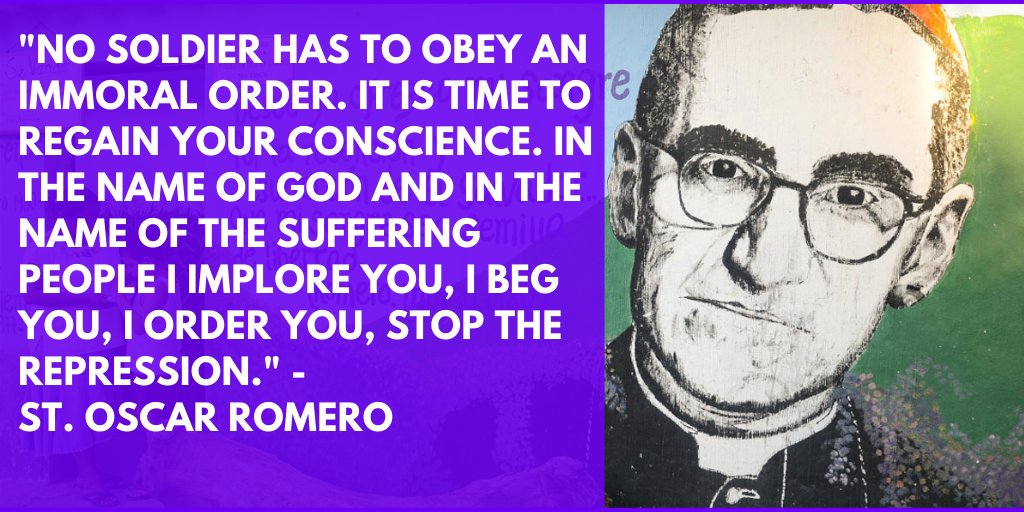

The prophetic voice of individual church leaders further galvanized resistance. Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador is the most globally recognized example. During his tenure, his weekly homilies were broadcast over radio across the country, serving as an alternative source of news that publicly denounced the violence and political assassinations carried out by the military and death squads.

His sermons transformed the pulpit into a public forum for human rights advocacy, culminating in his famous plea to soldiers: “I beg you, I beseech you, I order you: in the name of God, stop the repression!“

His subsequent assassination in 1980 only solidified his status as a martyr for justice and strengthened the resolve of local priests, nuns, and lay base communities (CEBs) who carried on the defense of the poor at the grassroots level.

Resistance Identity in Poland

Beyond Latin America, the Catholic Church was indispensable in challenging Soviet authoritarianism, most notably in Poland. Under Communism, the Church became the spiritual embodiment of Polish national identity and resistance against Soviet domination.

The 1978 election of Cardinal Karol Wojtyła as Pope John Paul II, the first Slavic pope, was a powerful blow to the Soviet system. His visits to his homeland, drawing millions into public gatherings, lifted spirits and provided a moral sanctuary for the Solidarity trade union movement.

Churches served as protected spaces where opposition meetings, underground education, and uncensored discussions could take place, especially during periods like Martial Law (1981-1983). Priests like Father Jerzy Popiełuszko held popular “Masses for the Fatherland,” providing a public platform for anti-Communist sermons and drawing huge crowds, embodying the nonviolent resistance that characterized the Solidarity trade union movement.

The Church often acted as an intermediary between the Communist authorities and the opposition (workers and intellectuals), particularly during crises. It helped to ensure the nonviolent nature of the opposition, preventing bloodshed that would have given the regime a pretext for brutal military suppression, as seen in other Soviet bloc countries.

Moral Positioning

In all these contexts, the Church’s advantage was its spiritual authority. By defining human rights not as political demands, but as requirements of inherent human dignity derived from natural law and God’s creation, it elevated the discussion above partisan politics. This moral positioning granted its members a degree of protection and its message a universal resonance that ultimately prevailed over darker forces.