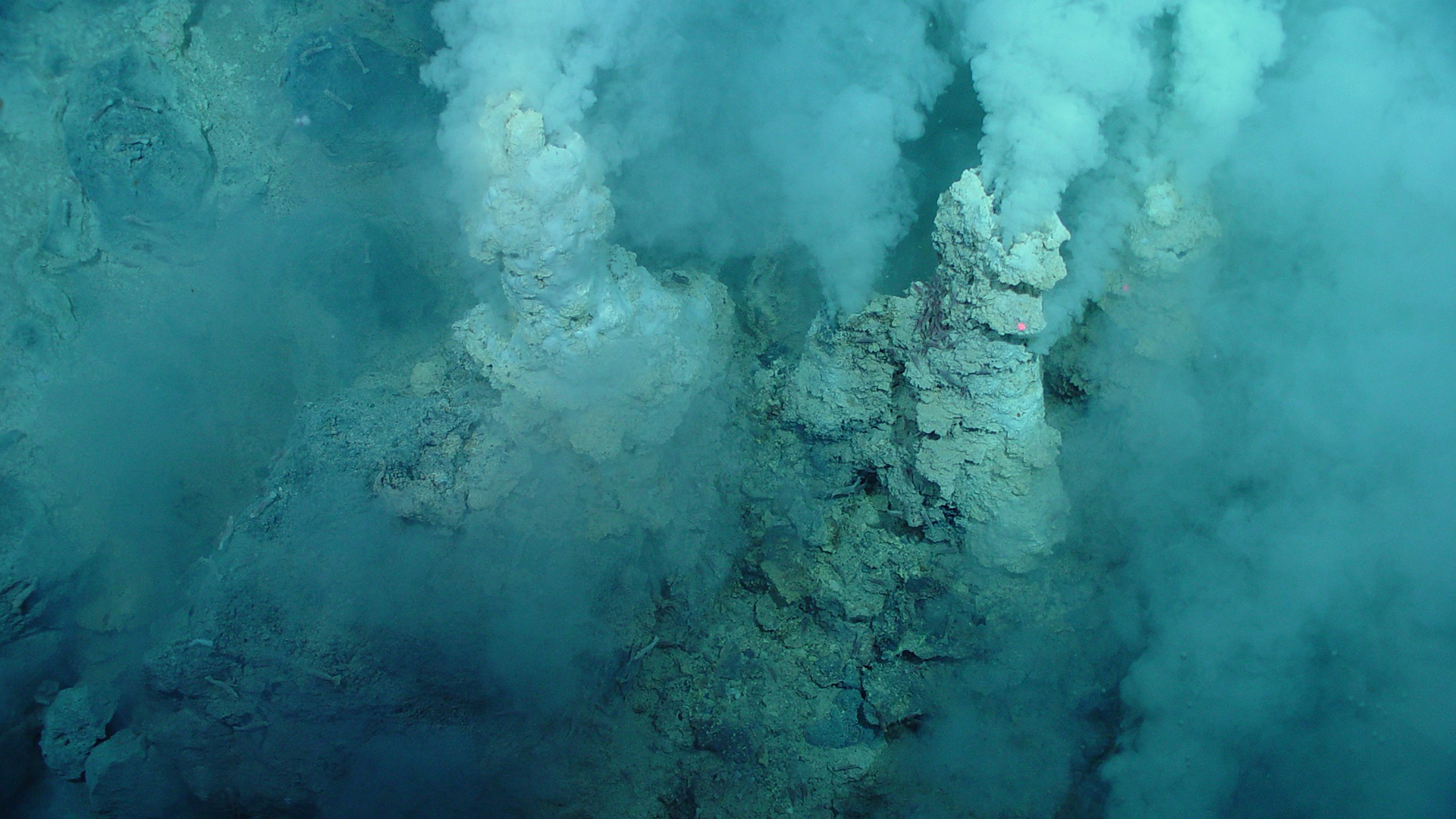

Photo of deep-ocean hydrothermal vents of intense interest to mining companies by Dr. Bob Embley, NOAA PMEL.

United States Skirts Multilateralism on Seabed Mining

With an executive order and broad interpretations of a 1980 law, the U.S. government now claims authority to issue mining permits in waters outside U.S. jurisdiction.

The United States stunned delegates to the International Seabed Authority toward the end of their annual meeting in March with news that signaled a willingness to completely sidestep the intergovernmental regulatory body.

The International Seabed Authority is an autonomous multilateral body charged with protecting and regulating the mining of the seabed in open ocean beyond national boundaries. In their annual meetings, this year held in Kingston, Jamaica, from March 17–28, the delegates discuss drafts of regulations for the mining of minerals in international seabed.

A key goal of this year’s meeting was to further develop the rules, regulations, and procedures that would govern commercial mining on the ocean floor, a fragile ecosystem. In her opening remarks, the secretary-general of the ISA, Leticia Carvalho, emphasized the importance of transparency, inclusivity, and a shared commitment to the sustainable use of marine resources.

On day ten of an eleven-day session of the ISA, the U.S. Subsidiary of The Metal Corporation (TMC) shocked the world with an announcement that it had formally initiated an application under U.S. law with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for permits for deep seabed mining–in international waters.

NOAA is overseen by the Department of Commerce, led by its secretary, Howard Lutnick. Secretary Lutnick, before his appointment by President Trump, was the CEO and chair of Cantor Fitzgerald, an investment firm with holdings in extractive industries. That firm had been engaged as financial advisors to TMC, and an analyst of the firm, Matthew O’Keefe, continues to participate in TMC’s quarterly earnings calls.

The U.S. government’s willingness to skirt multilateralism was made explicit on Apr. 24 with an executive order by Pres. Trump: “Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources.” The executive order states that “it is the policy of the United States to advance United States leadership in seabed mineral development by …establishing the United States as a global leader in responsible seabed mineral exploration on seabed mining encouraging the practice in both U.S. and international waters.”

In defiance of the regulatory authority of the ISA and the countries that comprise the ISA, the executive order directs NOAA to “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits in areas beyond national jurisdiction.”

Despite its mandate to work on ocean conservation, NOAA issued its own statement praising the executive order, describing deep seabed mining as “the next gold rush,” and celebrating Trump’s decision to “unlock access to critical deep seabed minerals.”

The Trump Administration’s legal justification for permitting mining beyond U.S. jurisdiction relies on, in addition to the recent executive order, the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act. That U.S. law, passed by Congress in 1980, asserted jurisdiction over U.S. citizens to prevent them from participating in reckless deep-sea mining abroad, a law which was to be in force until a more comprehensive Law of the Sea Treaty could be negotiated. The Law of the Sea Treaty morphed into a United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which established the ISA, but the United States never ratified that treaty.

UNCLOS came into force in 1994, and as of 2024, had 169 signatory countries. The full implications for international law of this new U.S. posture remain to be seen.

The head of the ISA responded on April 30 in a 15-paragraph statement criticizing the U.S. executive order to fast-track deep-sea mining in the oceans outside of U.S. territorial waters. “No state has the right to unilaterally exploit the mineral resources of the area outside the legal framework established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,” said Carvalho. “It is common understanding that this prohibition is binding on all States, including those that have not ratified UNCLOS.”

“It’s worth noting that the US Executive Order refers to Unleashing America’s Offshore Minerals and Resources,” Carvalho said. “However, this can only refer to resources found on the US seabed an ocean floor because everything beyond is the common heritage of humankind.”

“This means we are all stakeholders to what happens in the deep sea. It also means that any unilateral action not only threatens this carefully negotiated treaty, and decades of successful implementation and international cooperation, but also sets a dangerous precedent that could destabilize the entire system of ocean governance.”