Water and the Keystone XL Pipeline

The following article, published in the September-October 2014 NewsNotes, was written by Christiana Z. Peppard, Ph.D.; it was prepared in response to readers’ reactions to the World Watch column in the May-June Maryknoll magazine, which focused on the faith community’s actions to protest the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

The following article, published in the September-October 2014 NewsNotes, was written by Christiana Z. Peppard, Ph.D.; it was prepared in response to readers’ reactions to the World Watch column in the May-June Maryknoll magazine, which focused on the faith community’s actions to protest the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

The tar sands of Alberta, Canada, are a tantalizingly proximate source of crude oil that can be deployed to help sate the rather gluttonous energy appetite of the United States. Extraction of bitumen from Alberta’s tar sands is controversial on social and environmental fronts in the U.S. and Canada—even as it is considered desirable by strong economic and political interests in both countries.

Recently, a new concern has crested into public consciousness: What is the water impact of KXL? Two themes percolate here: the question of fresh water depletion, and the possibility of contamination. As Yale E360 pointed out, the extraction process uses profligate quantities of fresh water:

In 2011, companies mining the tar sands siphoned approximately 370 million cubic meters of water from the Athabasca River alone, which was heated or converted into steam to separate the viscous oil, or bitumen, from sand formations. That quantity exceeds the amount of water that the city of Toronto, with a population 2.8 million people, uses annually.

Moreover, this use of water is known as “consumptive use”: it cannot re-enter the watershed in meaningful ways after production of crude oil. (Even if the water is re-used in the extraction process, it is not suitable to re-enter ecosystems and is certainly not potable for domestic use.) Like mountaintop removal for coal, extraction of Alberta’s tar sands is a form of strip mining that has destroyed ancestral lands and left toxic byproducts that pollute the area’s remaining ecologically sensitive Boreal forests and wetlands. And this form of crude oil burns dirtier—emitting more greenhouse gases—than other types of fossil fuels.

For most U.S. residents, however, the ecological impacts of crude oil extraction from tar sands are out of sight and out of mind. Here, attention focuses primarily on the as-yet unconstructed northern segments of the KXL pipeline, which since 2012 have been under scrutiny by governmental agencies and environmental watchdogs. Recent furor focuses on potential water impacts of the proposed segment that passes through the northern part of the Midwestern United States.

In 2011, the proposed pipeline segment was approved by the state of Nebraska but was denied a permit by the federal government in January 2012, for reasons that included potential damage to sensitive soils and possible contamination of important groundwater sources.

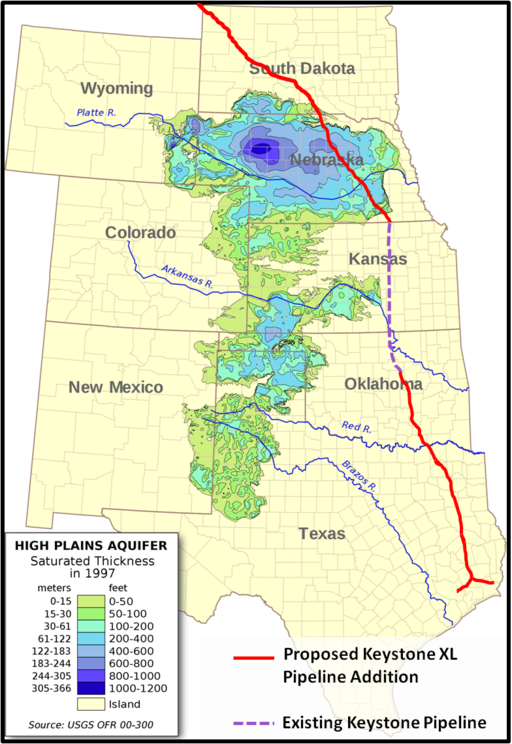

The biggest hydrological concerns center on two specific subterranean formations: the High Plains Aquifer, an enormous storehouse of groundwater that includes the Ogallala Group and is a source of water for nearly 30 percent of the country’s agricultural products; and the ecologically sensitive Sand Hills region, whose shallow groundwater could be especially susceptible to contamination in the event of a spill. In rejecting the KXL application in 2012, the federal government indicated that more thorough environmental impact assessments were needed and that re-routes of the pipeline should be considered to avoid possible deleterious impacts on vital groundwater supplies.

A re-routed version of the pipeline was proposed by Keystone and approved by Nebraska Governor Dave Heineman in 2013. According to those entities, the re-route “avoids the Sand Hills,” where shallow groundwater might quickly be contaminated by any potential spill. The proposed pipeline would still “cross the High Plains Aquifer, including the Ogallala Group” but, the company insists, “impacts on aquifers from a release should be localized and Keystone would be responsible for any cleanup.” With the Sand Hills issue circumvented, Keystone is betting on the low probability of an Ogallala-region spill and efficacious cleanup of any such event. This raises the question: What is the likelihood of a spill, and what impacts on the aquifer could it entail?

Analysis of the likelihood of spills differs between Keystone and the U.S. federal government’s assessments. A 2010 federal survey notes that “spills are likely to occur during operation over the lifetime of the proposed project” from “the pipeline, pump stations, or valve stations,” and it estimates a rate of “1.18—1.83 spills greater than 2100 gal/yr for the entire Project.” (Spills of any size were estimated at a frequency of 1.78—2.51 per year.)

Unsurprisingly, TransCanada’s estimates of spill frequencies were significantly lower, concluding that 0.22-1.38 per year were likely from the pipeline itself. Their estimate did not include leaks from valve stations—a significant omission, since according to the government, “the existing Keystone Oil Pipeline System has experienced 14 spills since it began operation in June 2010,” one of which occurred at a North Dakota pump station and leaked 21,000 gallons of crude oil.

Beyond number games, what are the chemical components and toxicological implications of potential spills in these regions? Crude oil from tar sands is known as bitumen, and in order to transport it smoothly it must be mixed with other chemical products known as diluents to create a composite product known as “dilbit.” Leaks of other dilbit pipelines, such as Michigan’s 2010 Enbridge spill, suggest that oil plus diluents can leak into surrounding areas; according to the EPA, those additional chemicals include “benzene, naphtha or natural gas condensate” and can leave traces of “polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals,” which “could be slowly released back into the water column for many years after a release and could cause long-term chronic toxicological impacts.” The Natural Resources Defense Council describes dilbit as “a more abrasive and corrosive mix” than conventional oil sources. A study released by NRDC in 2011 indicated that Alberta’s pipeline system for tar sands crude oil had 16 times the number of spills resulting from pipe corrosion when compared to U.S. onshore pipelines for conventional oil sources.

TransCanada has skirted the federal government’s request for advance disclosure of those chemicals, insisting instead that, “in the event of a spill, appropriate authorities would have timely access to product characteristics.” The company has also agreed to absorb all spill-related costs and will offer, on request, chemical testing of well water for landowners with crops or livestock within 300 feet of the pipeline. The company assures farmers that once the pipeline is installed, crop growth could continue short of the fifty-foot right-of-way perimeter.

Defenders of KXL rightly point out that segments of the pipeline already exist and exhibit little to no evidence of groundwater contamination. Critics respond that the scale and centrality of the Ogallala Aquifer has no parallel in the pipeline’s southern sections.

On the one hand, the Ogallala Aquifer is rapidly declining in volume due to agricultural demand. Possible seepage of crude oil into the aquifer would have dramatic consequences for the agricultural economy of the Midwest, because of the finite nature of the water in the aquifer and because its subterranean location pose major difficulties for effective cleanup of crude oil spills. Moreover, any subterranean cleanup would also depend in part on the nature of the diluting agents, which TransCanada would only disclose after a spill. On the other hand, some commentators acknowledge that construction of KXL is incrementally preferable to aboveground transport of dilbit crude oil via railways or truck transport, which are subject to higher rates of leaks, crashes, and human error.

Lobbyists and classical economists suggest that the short-term benefits of job creation and proximate sources of crude oil are worth staking a limited risk to the aquifer. But ecological economists, water advocates, and environmental policy strategists correctly observe that the use of tar sands as a fuel source does little to move the U.S. economy off of fossil fuel reliance; and the economies of the Midwest depend upon the integrity of soils and water sources, for which there are no viable substitutes.

What is to become of the proposed re-route of the KXL pipeline? The federal permitting process is in a state of limbo and will likely remain so until after the U.S. election season, while politicians rhetorically deploy the KXL debate to their constituencies in the short-term pursuit of re-election.

Citizens need to focus on longer-term horizons. Proximate fossil fuel supplies that power our economies and create jobs are valuable in today’s energy economy. Is it worth risking the integrity of economically productive and life-supporting groundwater sources? Who stands to benefit, and who will bear the burdens?

Sources in addition to government documents:

Map showing the proposed route of the pipeline across the aquifier reprinted through the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.