Right to communication vs. freedom of speech

While freedom of speech is a basic right recognized (though not always respected) internationally, progressive governments in South America are working to go beyond that.

The following article appeared in the September-October 2013 issue of NewsNotes.

While freedom of speech is a basic right recognized (though not always respected) internationally, progressive governments in South America are working to go beyond that. They believe that their citizens have a right to communication, not only free speech but access to the means of communication as well. Instead of allowing a small number of corporations to control the vast majority of their TV and radio stations, newspapers, and other media outlets, these governments are allowing more people to broadcast their ideas through the creation of more public and community-run stations. Large media corporations that stand to lose profits due to the increased competition brought by these changes have falsely portrayed the initiatives as attacks on free speech.

Latin America has a long history of concentrated media ownership. For decades, the proprietors were politically influential families, though in the last 20 years, many have morphed into massive international conglomerates with interests not only in media and communications, but banking, industry and other areas. Argentine media researcher Martin Becerra reported in 2010 that on average, “more than 82 percent of all information and communications activities [in Latin American countries] are controlled by the top four operators.”

This media concentration limits the diversity of viewpoints that people are exposed to and the amount and quality of political debate in those countries. As Becerra states, “I believe that if control of the media was not so highly concentrated, the situation of inequality in Latin America would be more actively challenged.” Carlos Ciappina, secretary of the Journalism and Social Communication School of the National University of La Plata, said, “Democracy and media monopolies are two things that simply cannot go together. There is no true democracy if the media is not democratized. Because if the media are not democratized, very few speak. And those who speak have an enormous influence, but nobody voted for them.”

To allow for a richer public debate, the UN Commission on Human Rights has called on all countries to “encourage a diversity of ownership of media and of sources of information, including through transparent licensing systems and effective regulations on undue concentration of ownership of the media in the private sector.”

Venezuela was the first to move in this direction in 2000 when it passed the Organic Telecommunications Law that aims to “guarantee access to communication as a human right.” It created three types of media: private, public and community and guaranteed that each form of media would have access to the public airwaves. One result has been a surge in the number of media outlets: from 331 commercial and 11 public access FM stations, in addition to 36 private and eight public television broadcasters in 1998 to 499 private, 83 public access, and 247 community radio stations, as well as 67 commercial, 13 public service, and 38 community television concessions by April 2012. In addition, the government has provided tens of thousands of free laptop computers to schoolchildren and has opened thousands of “Infocenters” (free computer and Internet access stations) nationwide.

In Uruguay, the Congress passed the Law for Community Broadcasting in 2007 that formally recognized community TV and radio as part of the nation’s airwaves; before this law, these alternatives sources of information were considered illegal. Since passage of the law, more than 100 communities have started their own radio and/or TV stations.

Ecuador’s Organic Communications Law, passed in June of this year (though not yet sanctioned by President Correa), redistributes the country’s radio frequencies, providing 33 percent to private media, 33 percent for public media and 34 percent for community media (in 2012, 71 percent of radio and 85 percent of TV was privately owned). It limits any single person to owning no more than one AM radio station, one FM station and one television station. To encourage national cultural production, the law requires that at least 60 percent of daily broadcasting be nationally produced and 50 percent of music played should be produced, composed or performed in Ecuador.

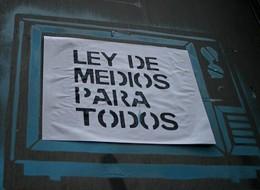

Argentina passed a similar law in 2009, the Audiovisual Communications Services Law, which distributes broadcasting licenses in the same percentages as Ecuador, though it establishes a higher limit for individual ownership, allowing a maximum of 10 concessions.

The massive media conglomerates that have dominated the airwaves for decades are threatened by these changes because the laws will increase their competition. In response, these media have used their considerable influence to paint these laws as anti-free speech. Other large media conglomerates in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere simply repeat these false charges without context or explanation.

While the mainstream media portray the governments passing these new laws as dictatorial and against free speech, those who study South American media like Ciappina disagree: “I would say the opposite. Today, in countries like Venezuela or Argentina, there has never been so much freedom of speech.”

Photo: Argentina Indy Media