Peru: Toxic spill in mining community

The following story was published in the September-October 2012 NewsNotes.

In the last edition of NewsNotes, we reported on the two deaths and many injuries that occurred in the Peruvian province of Espinar when people protested the Anglo-Swiss mine Xstrata. In early July, violence erupted once again in the region of Cajamarca, this time leaving five protesters dead and many others wounded in demonstrations against the Denver-based mine, Newmont. In a more recent mining conflict, the town of Santa Rosa de Cajacay is still recovering after a toxic spill by the Antamina mining group, which includes Xstrata. The following story was published in the September-October 2012 NewsNotes.

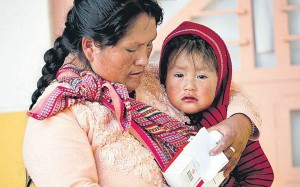

Photo from the website regionlimaaldia.com

On July 25, the Antamina pipeline carrying copper concentrates and toxic compounds burst and spilled 45 tons of its contents into the village of Santa Rosa de Cajacay. After realizing what had occurred, Abraham Balabarca, who was constructing a house nearby, ran with others to a facility managed by the mine to try and stop the flow. They found the door locked and that the security guard had no key. “By the time someone pried open the lock with a crowbar, the town was shrouded in a toxic cloud,” reported the Associated Press (AP) in an August 16 article, Townsfolk sickened after Peru toxic spill.

Antamina’s director of community relations provided only absorbent cloth to villagers recruited to help clean up the spill. The AP article cited the work of an environmental chemist and toxicology professor at the University of Idaho-Washington State University, Greg Moller, who called the lack of protective gear “unethical and irresponsible.”

An estimated 350 villagers “[were] treated for headaches, respiratory tract bleeding, nausea and vomiting, according to the mayor’s office.” Pregnant women, and other vulnerable persons, including at least 69 children, were among those negatively affected. According to the AP article, Dr. Juan Villena, dean of Peru’s College of Physicians, reported that some children in the town had “serious muscular and respiratory problems, bleeding from the nose.”

In contrast, in a radio interview, Health Minister Midori de Habich said there have been no serious threats to people’s health. In an August 8 meeting between villagers and company executives, Antamina agreed to establish a health committee to provide compensation to victims. Villagers whose emergency treatment was paid for by Antamina, however, are concerned that their health reports may be manipulated – after requests for the results of their blood tests or any other documentation that would attest to their hospitalization were denied. They are now asking that they be treated by more neutral doctors to provide an accurate, trustworthy report to the committee.

At the meeting, Antamina – which has amassed a fortune in the past 10 years – agreed to construct the reservoir that in 2000 had been the condition for the mining group to lay the pipeline in the first place.

According to an August 22 blogpost by GRUFIDES, a Peruvian non-governmental organization, the state was in part to blame for the reservoir not being constructed. The manner in which Antamina and the Peruvian government have behaved towards the Cajacay community is typical in regards to extractive industry projects.

“The cry of the earth and the cry of the poor are one.” (Chapter 10, 2004 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church) Unfortunately, as the explosion of extractive industries ricochets throughout the world, this cry resounds ever more loudly. Who is listening?