IFC standards have subpar outcomes

The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private lending arm of the World Bank, is the largest department of the five World Bank entities. In recent years, due to pressure from civil society, and in some cases from private industry, the IFC developed performance standards related to social and environmental sustainability to manage environmental and social risks. The practical performance of these standards falls short.

The following piece was published in the November-December 2014 NewsNotes.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private lending arm of the World Bank, is the largest department of the five World Bank entities. In recent years, due to pressure from civil society, and in some cases from private industry, the IFC developed performance standards related to social and environmental sustainability to manage environmental and social risks. The practical performance of these standards falls short.

One enigmatic case that highlights the shortcomings of the performance standards is from the Aguán Valley in Honduras, where a palm oil project developed by Dinant Corporation is linked to the killings of 100 farmers, forced evictions of many more, and kidnappings. (See May-June 2013 NewsNotes.) Even before the project began, the area had a long standing conflict over land; the communities never gave free prior or informed consent to the corporation.

The funding from the project came from the IFC as well as German Investment Development Corporation (DEG) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) through a Honduran financial intermediary bank called FICOHSA. DEG and the IDB withdrew their funds in 2011 over allegations of human rights abuses and land disputes, but the IFC continued its funding.

The Compliance Advisory Office (CAO), an independent watchdog for the IFC, received a complaint on behalf of the community. After investigating, the CAO issued a report in January 2014 which stated that the IFC failed compliance at every stage of the investment process: assessment, supervision, and evaluation. The CAO found that the IFC ignored news implicating Dinant in egregious crimes or did not do the proper research. It also found that the IFC continues to be in breach of disclosure and failed to consult the communities. When the IFC saw a draft CAO report, the IFC asked the CAO to remove and cover up some of its findings related to due diligence.

After site visits, the IFC found inadequate implementation of its social and environmental standards but at no point penalized or compelled Dinant to come into compliance. It also inadequately supervised Dinant’s security force of 300 people.

Lastly, the CAO report found that the IFC culture discouraged staff from acting or speaking up when violations occur. The culture also encouraged lending at the expense of social and environmental risk.

Another case in Cambodia relates to a sugar plantation project in Kampong Speu, just southwest of Phnom Penh. The IFC lent money to the ANZ Royal Bank in December 2010 to expand its investments in the agricultural sector. It turns out that the project led to a massive land grab of 2,000 hectares belonging to approximately 1,100 families in 10 officially recognized villages of Amliang Commune and at least another five unrecognized villages. The company also employed child labor.

In response to both these and other cases, the IFC published “Lessons Learned” on environmental and social risks. A civil society analysis found that the lessons highlight important suggested improvements to address legacy issues and incorporate a greater country security and conflict context into their lending practices. However they do not include changing IFC culture, ensuring consequences for environmental or social risks, reviewing the IFC portfolio for other risky projects, or giving greater attention to human rights risk assessments. The civil society analysis also raised concerns about how the lessons learned would be implemented.

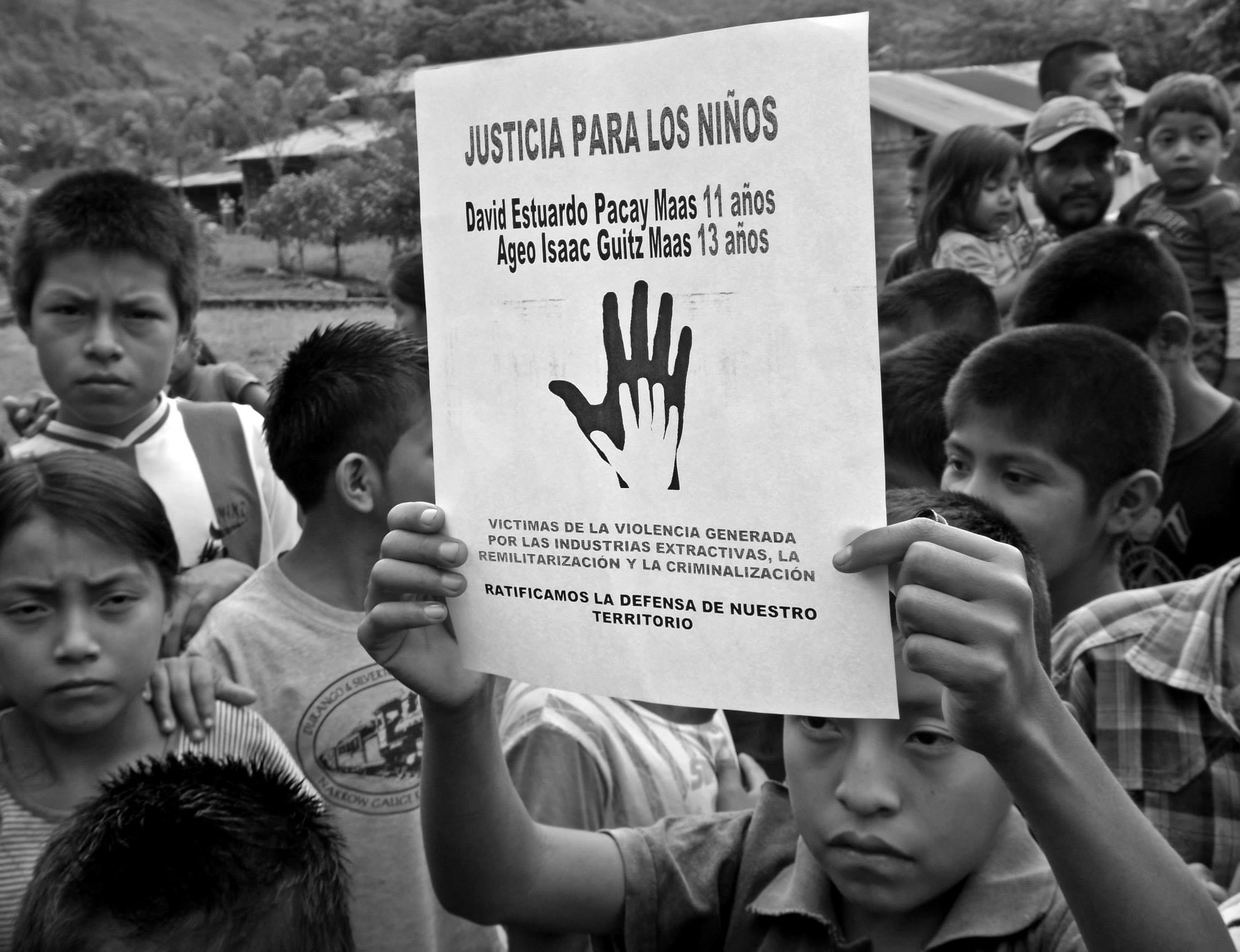

The Hydro Santa Rita dam project in Guatemala’s Alta Verapaz province is opposed by the local indigenous people; the communities own their land and never gave free prior and informed consent to the project. In August, approximately 1,600 police descended on the communities near the Delores River, forcing many people to flee to the hills. This followed a series of other events where community members were threatened or killed. (See September-October 2014 NewsNotes.)

The project is funded through a financial intermediary, Latin Renewable Investment Fund, by the IFC, the DEG, and the Dutch development bank FMO. Community representatives filed complaints in October 2014 with the three funders. MOGC staff recently accompanied community members to meet with staff at the World Bank and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

It is clear that the IFC does not have the ability to hold accountable financial intermediaries, which it made clear at a panel presentation as part of the World Bank Civil Society Forum in October. One IFC representative commented that they can’t reach the small and medium enterprises themselves so they depend on financial intermediaries and sometimes that has negative consequences.

The failure of the IFC to ensure that performance standards are met is also compounded by some of the vagueness of the standards themselves.

Another great concern is that the IFC standards are held up as a guide for other bodies trying to create environmental and social protocols. The new Green Climate Fund, intended to help developing countries to adapt and mitigate the worst impacts of climate change, will include the IFC Performance Standards in the interim until it is able to develop its own standards. This is particularly worrisome because the Dinant and the Hydro Santa Rita projects were approved as clean development mechanism projects under the Kyoto Protocol. If projects meant to assist communities ultimately cause more harm, do financiers actually have the ability to guarantee environmental and social safeguards?

Other proposals that will use the IFC Performance Standards include the Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment (though civil society engagement has ensured that the IFC standards will not be the only safeguard benchmarks). The Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance is also proposing the IFC Performance Standards.

In the case of the IFC lending, at least the CAO acts as a watchdog to ensure that the performance standards are met. Without such a watchdog agency, it is not clear that human rights, environmental protections, and other social safeguards such as Free Prior and Informed Consent for indigenous communities are met.