Cambodia: Worker rights abuses in garment industry

Opportunities for Cambodian workers to share in the prosperity of that country’s garment industry come at the price of exploitation and abuse.

The following article, written by Maryknoll Affiliate Chris Smith, a Washington, D.C.-based writer, was published in the May-June 2015 NewsNotes.

Cambodia’s global exports reached $6.5 billion in 2013, with $4.96 billion (76 percent) coming from the garment and textile industry. The garment sector figure rose to $5.7 billion in 2014. The garment industry in Cambodia represents a major source of the country’s non-agrarian jobs. Over 90 percent of the 700,000 workers in the garment sector are women.

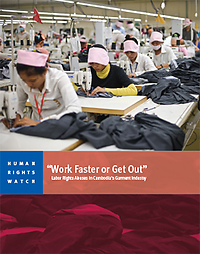

But the opportunities for workers to share in the prosperity of the industry come at the price of exploitation and abuse. A March 2015 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report (“Work Faster or Get Out”: Labor Rights Abuses in Cambodia’s Garment Industry) documents a story of wage and working conditions abuses, child labor law violations, discrimination against pregnant workers and sexual harassment, and union busting. Despite a strong labor law passed in 1997 designed to protect Cambodian workers, enforcement is weak and the use of short term contracts serves to control employees, avoids payment of earned benefits and obstructs union organizing.

The HRW report was based on interviews with 342 people that included workers, union representatives, factory representatives and Cambodian Labor Ministry officials. The report documents a wide range of issues:

Overtime and wages: Although Cambodian law limits the work week to 48 hours, with a maximum two hours overtime per day (for a six-day work week), most workers interviewed said that they often far exceeded the 12-hour overtime weekly limit. The demand to meet production targets meant that workers were pressured not to take bathroom or rest breaks, and special bonus incentives to meet targets were often unpaid.

Child labor: Although Cambodian law restricts employment to those age 15 and above (with jobs limited to light work and an eight-hour daily maximum) and requires registration and proof of age records by employers, the reality found by HRW researchers tells a different story. Many under-age children started between 12 and 14 years old, driven by the lack of educational access and/or the need to supplement their family’s income. They often were paid less than the minimum wage and were instructed to hide from view when “visitors” came to the factory.

Union busting: The report found evidence of concerted efforts to break unions at 35 factories since 2012. Multiple union representatives testified that “as soon as workers initiated union-formation procedures, factory management would dismiss union officer-bearers or coerce or bribe them to resign, thwarting union formation.” Since December 2013 Cambodia’s Ministry of Labor introduced new obstacles to licensing unions, delaying the certification of unions and allowing management time to use retaliatory measures against union leaders. Additional measures to raise the threshold for the number of workers required to gain recognition and allow the Ministry of Labor to suspend union registration without judicial review also served to restrict the rights of workers to organize and form a union.

Women facing sexual harassment and discrimination against pregnant workers: Although the law in Cambodia provides for three months of maternity leave and maternity pay if employed for one full year (without interruption), the pervasive use of short-term contracts often thwarts any meaningful enforcement of these protections for pregnant employees. These workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Their condition meant that denial of bathroom and rest breaks could easily lead to dismissal for failure to meet production targets. One Phnom Penh factory worker told HRW: “It doesn’t matter whether you are pregnant or not – whether you are sick or not – you have to sit and work. If you take a break, the work piles up on the machine and the supervisor will come and shout. And if [a pregnant] worker is seen as working ‘slowly’ then her contract will not be renewed.” Sexual harassment is common, with an ILO survey showing that 20 percent of women report sexual harassment leading to a “threatening work environment.”

One of the critical issues that magnifies the risk for workers in developing countries is the extensive use of subcontractors to factories. In many cases not directly authorized by international brands, these subcontractors often escape the monitoring regime of Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), the third party auditing firm that inspects garment factories for the international companies. The need to meet quotas and/or rush orders leads to supplemental work being handed off to subcontractors who use more casual hiring practices and shorter-term contracts that contribute to weaker protections for worker rights. While BFC provides critical information to international brands who are serious about monitoring their supply chain, individual audit reports are not available to unions and workers, thereby hampering their ability to confirm that worker complaints are accurately reflected in the reports. Nevertheless, BFC launched a “Transparency Database” in March 2014 to provide enhanced disclosure of company audits, and the existence of a third party auditing system provides an important tool for holding international brands accountable for protecting the rights of workers who make their products.

Ultimately, accountability begins with international brands like Gap, Marks and Spencer, Joe Fresh, Adidas and H & M. These brands have a mixed record, with Adidas disclosing its supplier list in 2007 and H & M by 2013. Gap, Marks and Spencer and Joe Fresh do not yet disclose this information publicly. In addition, companies need to publicly disclose what corrective action was taken in cases of abuses and whether any improvements are being sustained over time.

The Cambodian government has also fallen short in its accountability to enforce laws protecting workers. Labor inspectors told HRW that bribes in exchange for favorable reports were common, and the Labor Ministry’s own data showed fines were imposed on just 10 factories between 2009 and 2013.

The Human Rights Watch report on the Cambodian garment industry mirrors similar reports documenting worker rights abuses in many other industries and developing countries. Yet it also underscores the fact that existing mechanisms provide a framework for enhancing protections for workers to maintain employment in a safe, stable and sustainable environment that respects their dignity and internationally-protected rights. The joint efforts of international brands, the Cambodian government, Better Factories Cambodia, unions and workers and international NGOs can all contribute to ensuring that Cambodian garment workers receive the rights they are entitled to under both international law and a just and equitable economic system.