Bolivia: At the crossroads

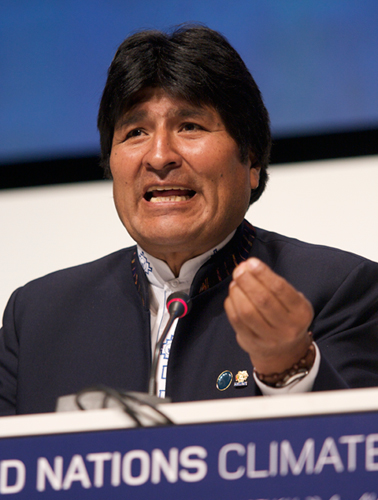

Recent Bolivian presidential and legislative elections showed the consolidation of the political power of the charismatic indigenous leader Evo Morales and his Movimiento a socialismo (Movement to Socialism, MAS) party in electing him to serve an unprecedented third term with a resounding 61 percent of the popular vote.

The following piece was prepared by Fr. Stephen P. Judd, MM and published in the November-December 2014 NewsNotes.

Recent Bolivian presidential and legislative elections showed the consolidation of the political power of the charismatic indigenous leader Evo Morales and his Movimiento a socialismo (Movement to Socialism, MAS) party in electing him to serve an unprecedented third term with a resounding 61 percent of the popular vote. With this percentage he almost matched the 62 percent he won in 2009. The populist leader Morales was elected to his first term in 2005 with a 54 percent total.

Unofficial early tabulations from the October 12 elections indicate that Morales captured the vote in eight of Bolivia’s nine departments. In the three largest populated departments – Santa Cruz, La Paz and Cochabamba – his totals surpassed predictions against a very weak opposition with well-known candidates like Samuel Doria Medina and former president Jorge Quiroga.

According to close observers of the Bolivian political process, the landslide victory can be attributed to a number of factors, chief among them the power of the popular indigenous social movements and, to a lesser extent, the robust economic growth in recent years. Bolivia is one of Latin America’s success stories with a rising average of six percent growth in gross national product. While mineral prices remain high on the world markets, this growth is expected to rise. On the economic front, the country’s reserves have surged to new heights.

As a result, average Bolivians have seen a marked improvement in the quality of life with increased buying power. Government social programs have contributed to the MAS government’s popularity enabling once excluded sectors of the populace to slowly but steadily acquire more economic security and recognition in a country that has always been among the most impoverished in the hemisphere. But, these valid explanations only tell part of the Bolivian success story, according to local political analysts like María Teresa Zegada and Jorge Komadina in a recent much acclaimed book, El espejo de la sociedad: poder y representación en Bolivia.

At an August book presentation here in Cochabamba at the Maryknoll Mission Center, both authors point to other factors that demonstrate the strengths but also the potential weaknesses of the Morales and MAS political power and its sustaining transformative potential for the future. On the one hand, the emergence of new social and political actors is symbolically visible in the makeup of the country’s Parliament. This is a body that truly reflects the ethnic diversity of the country. Yet, as Zegada and Komadina question, how representative of the country’s diversity are these elected officials of where true power resides? Many who presently occupy elected posts are veterans of the social movements and beneficiaries of the cultural capital promoted in official government circles. Lines of distinctions between the social and the political spheres have become blurred in Bolivian society making the country a test case for a new kind of democracy in Latin America.

Their analysis attempts to trace the vast changes in the country to the long term development of democratic institutions and conclude, rightly or wrongly, that over the past several years powerful corporate forces in the mining and transportation sectors wield an oversized influence on the political process able to press their claims and interests. Similarly, with many new laws generated by power concentrated in the executive branch, they raise questions of long range democratic sustainability when “corporativist” means of governance predominate.

Underpinning the analysis of friends and foes alike of the MAS government is its capacity to work toward unity in diversity, to recognize the pluralistic nature of society to reach a consensus and work toward the value of the common good. Certainly, some in the Catholic Church leadership and progressive pastoral agents continually stress the principles of Catholic Social Thought in terms of the pursuit of the common good, solidarity and subsidiarity quick to present a posture of constructive criticism to the changes in Bolivia. However, instead of playing the role of friendly critic, church leaders often adopt an adversarial stance vis à vis the government and the significant transformations underway in Bolivia.

At the same time more extremist radicalized sectors in the government fail to regard the Church’s historic role in the struggle for human dignity and the defense of human rights, intercultural dialogue and the outreach of the Church’s social programs in education and health. Such was the message of a book written in 2011 by Filemón Escobar, one of the founders of the MAS party and now a dissident, El Evangelio es la encarnación de los derechos humanos, which argues for the Church’s frequently ignored contribution to the recovery of democracy. The book proposes what many committed to societal transformations from a faith-based position consider a crucial question: How might there be a meeting of minds in a hoped-for national dialogue during the next few years to seek ways to become partners co-responsible in the process to create a new Bolivia?