Africa: Migration trends and patterns

There are numerous influences in Africa pushing and pulling people to migrate either within their country, or across, away from, or into the continent, spreading new ideas and changes in culture.

There are numerous influences in Africa pushing and pulling people to migrate either within their country, or across, away from, or into the continent, spreading new ideas and changes in culture. The following article was published in the July-August 2017 issue of NewsNotes.

Nowhere are the patterns, characteristics, and causes of migration more complex and misunderstood than on the continent of Africa. Recent media images of African migrants drowning in the Mediterranean Sea have given rise to an apocalyptic image of desperate people fleeing poverty and violence at home and subject to ruthless traffickers and smugglers along dangerous migration routes towards Europe. Not only does this image reinforce the general picture of Africa as a continent plagued by violence, war, and abject poverty, but it also furthers the stereotypes and myths about the reality of migration in general, and African migration in particular, that in turn influence the formulation of responses aimed primarily at managing and eventually curtaining the flow of people.

In recent years a number of global and African organizations have produced in-depth research on what is happening to the millions of African who are on the move. One major finding questions the myth that migration in Africa is an uncontrolled phenomenon largely driven by the desperation scenario of escaping from poverty and violence. While this may be true for some young African men, many more African migrants are driven by labor demand and perceived economic opportunities. Their migration takes place in a legal, orderly manner. Most people who are emigrating out of Africa are in possession of valid passports, visas, and other travel documents and are migrating for the same reasons as migrants from other part of the world – family, work, or study. More often than not they are coming out of countries with higher levels of economic development.

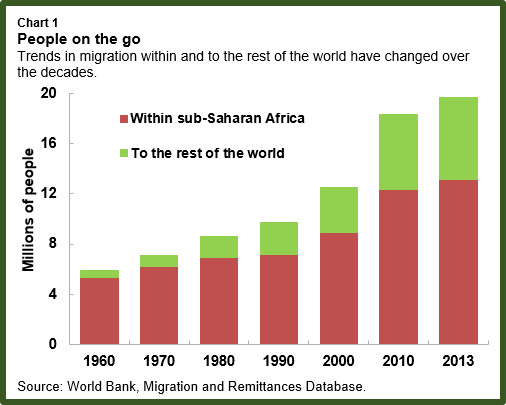

While the migration rate (migration-to-population) in Africa has remained steady over the last 23 years at about 2 percent, the number of migrants has increased due to the doubling of population in the same period. Today there are about 20 million migrants on the continent. The percentage of those who leave Africa has increased steadily from a quarter to a third of the total and by 2013 it stands at about 6 million people.

Migration by Africans is becoming a more complex and diverse process with more types of people on the move to a larger number of destinations both within Africa and to other countries around the world. It is impossible to reduce this complex phenomenon of human mobility to the drivers of misery and conflict. Some countries, like Morocco, are experiencing the simultaneous movement of migrants in, out, and through their countries. Ghana experiences internal migration, immigration, transit migration, and emigration to both within and outside of Africa. Over one million Chinese, seeking business opportunities and drawn by more open societies, are reported to have migrated permanently to the continent.

The form migration takes is also becoming more diverse as migrant laborer, traders, commuters, visitors and people working in frontier areas may all be on the same bus crossing one of Africa’s numerous borders. The older colonial model of push-pull migration related to labor demands is no longer adequate to capture the complexity of mobility in contemporary Africa.

Despite the continued existence of some of the world’s largest refugee camps in northern Kenya, the actual number of African refugees—people fleeing due to war or persecution—has decreased considerably since 1990. In 1990 about half of total migrants were refugees, and this share has declined to only about 10 percent by 2013. However, the number of internally displaced people is increasing. In total, 12.4 million people were internally displaced in Africa as a result of conflict and violence. This is 30 per cent of the total number of people internally displaced by conflict globally (48 million people) and twice the total number of African refugees (5.4 million people). Only recently have organizations like the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center begun to collect information on people displaced by development projects and slow-onset crises related to drought and environmental change.